Written by Verity Pooke, ESRC PhD Candidate in Social Policy at the University of Kent, and Clare Murphy, Director of External Affairs at the British Pregnancy Advisory Service

The focus of World Contraception Day is to improve awareness of all contraceptive methods available and enable everyone to make informed choices on their sexual and reproductive health. In this blog, authors of the recent article Emergency contraception in the UK: stigma as a key ingredient of a fundamental women’s healthcare product, published in the SRHM journal issue The elimination of stigma and discrimination in sexual and reproductive health care, give an overview of the article and call for the reclassification of emergency contraception in order to increase access.

It’s nearly 2 decades since progestogen-based EC was first made available to buy from behind the counter in UK pharmacies. The experience of other countries illustrates that women can use this product safely and without supervision. Today we call for emergency contraception to be reclassified so it can be sold straight from the shelf without a consultation, affording women the best chance of avoiding an unwanted pregnancy.

It now seems extraordinary that when this product was first manufactured, it wasn’t envisaged as a “back-up” or solely for “emergency” use, but as a product women having sex once a week or less could use as their regular method. It came in packs of 10. The idea, infact, was to reduce women’s exposure to hormones from using a daily pill that they may not want or need. This seems very far removed from where we are today.

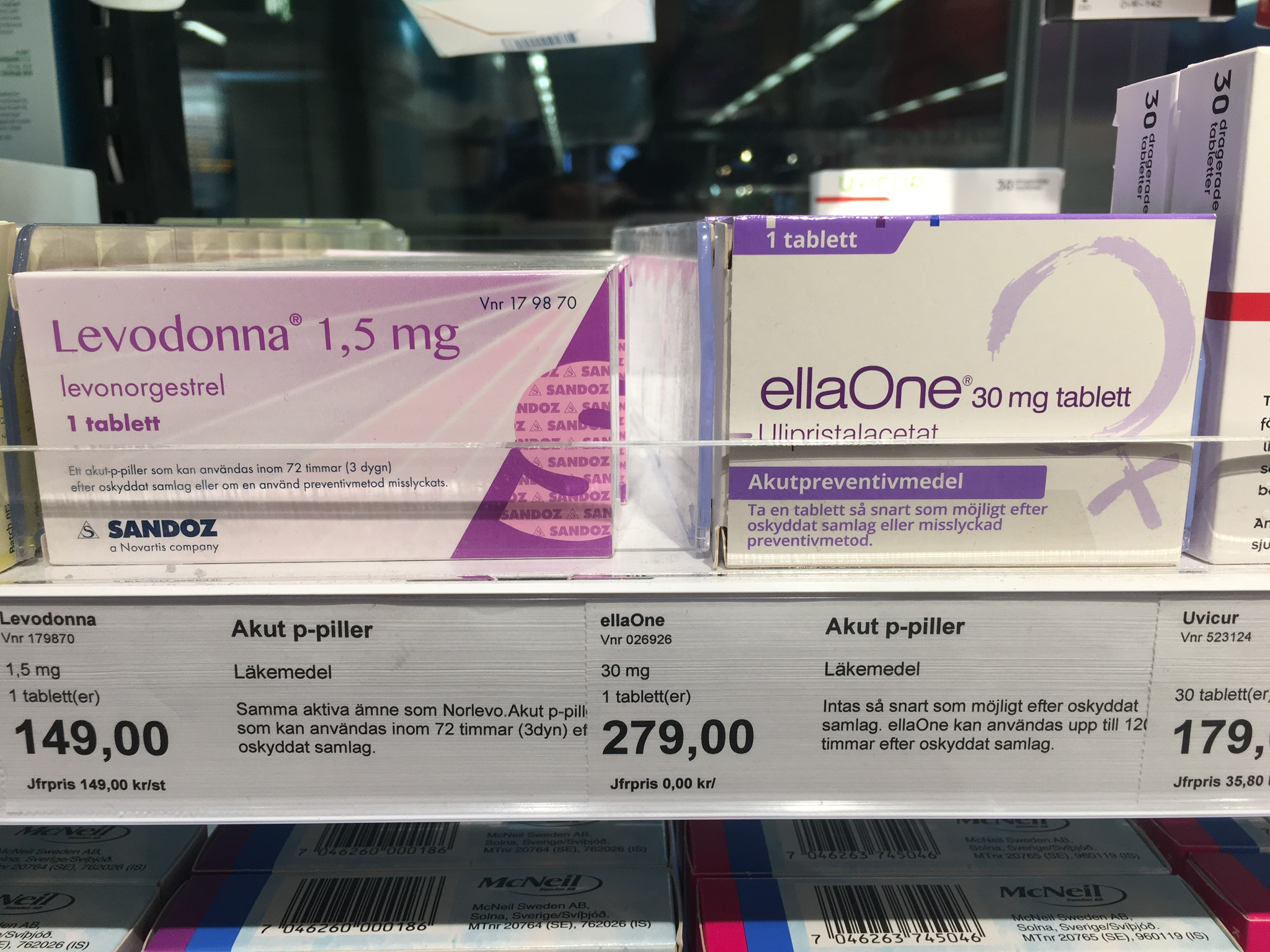

Wrapped up within this (now) one pill package is a whole host of attitudes towards women and their sexuality – the morning after pill has become a marker of “irresponsibility”, a product women are told they should use but should never need to use. In the UK, the pill was deliberately priced high at the outset to discourage women from using it. It was only in 2017, following a campaign from the British Pregnancy Advisory Service, that retailers agreed to reduce the cost. The high street pharmacy Boots initially refused to do so, on the basis that they did not wish to “incentivise inappropriate use”. The price did eventually drop – by more than 50% in some cases – but even so, it still remains disproportionaly high compared to its actual cost to produce.

One of the justifications for the continued high price is the fact that women must undergo a consultation before the pill can be sold. The length and content of this consultation will vary, but it is deemed an important opportunity to counsel a woman about other forms of contraception, the possibility of STIs, and address any safeguarding concerns.

It may well be that a woman will want further information on these issues. But the current framework of mandating a consultation, rather than providing information at a woman’s request, can act as a barrier to access. And mystery shopping exercises have illustrated that while pharmacists generally provide a swift and non-judgmental service where they can, they provide limited information about other contraceptive options, while the location of the consultation can also make the divulging of sensitive information unlikely. So we need to question whether the value of the consultation offsets the barrier to access it represents.

Presently, only a third of UK women use EC after an episode of unprotected sex. This means that EC is a significantly underutilised resource. Most women would prefer not to undergo a consultation and purchase the pill straight from the shelf, as they can in European countries including Sweden and the Netherlands, but also in the US and Canada.

There is no clinical reason to restrict women’s access to EC or insist she can only take it under the supervision of a pharmacist, but good clinical reason to facilitate her access. EHC is most effective the sooner it is taken; and we should be very clear what most effective means in this context – this isn’t about alleviating a headache or an episode of diarrhoea, as uncomfortable and unpleasant as those may be. It is about enabling a woman to avoid an unwanted pregnancy and the many consequences that may bring.

We believe the time has come to reclassify EHC as a General Sales List (GSL) medication so it can be sold straight from the shelf of a pharmacy or supermarket. In the late 1990s, Nicotine Replacement Therapies – now in the form of gums, pills and patches – were reclassified as GSL products by the UK’s medicine’s watchdog on the basis that there are no circumstances where it would be safer to smoke than to use these products – notwithstanding that there may be contraindications for some groups, or that the NRTs, particularly in their lozenge and gum form, could be attractive to very small children and could prove toxic. There are no contraindications to progestogen-based EC, and there are no circumstances where it is safer to be pregnant than to use it. Reluctance to increase access to EC is not based on health, but the persistent distrust of women and their capacity to manage their own sex and reproductive lives. It’s time to trust women.

Please note that blog posts are not peer-reviewed and do not necessarily reflect the views of SRHM as an organisation.